Efficiency is often spoken of as an unquestioned good. In corporate reports and investor briefings, it appears as a clean metric: lower costs, higher output, improved consistency. But efficiency looks different when viewed from the ground. In the tea fields of the South Rift across Kericho and Bomet, efficiency has a human face, and its consequences are far more complex than spreadsheets suggest.

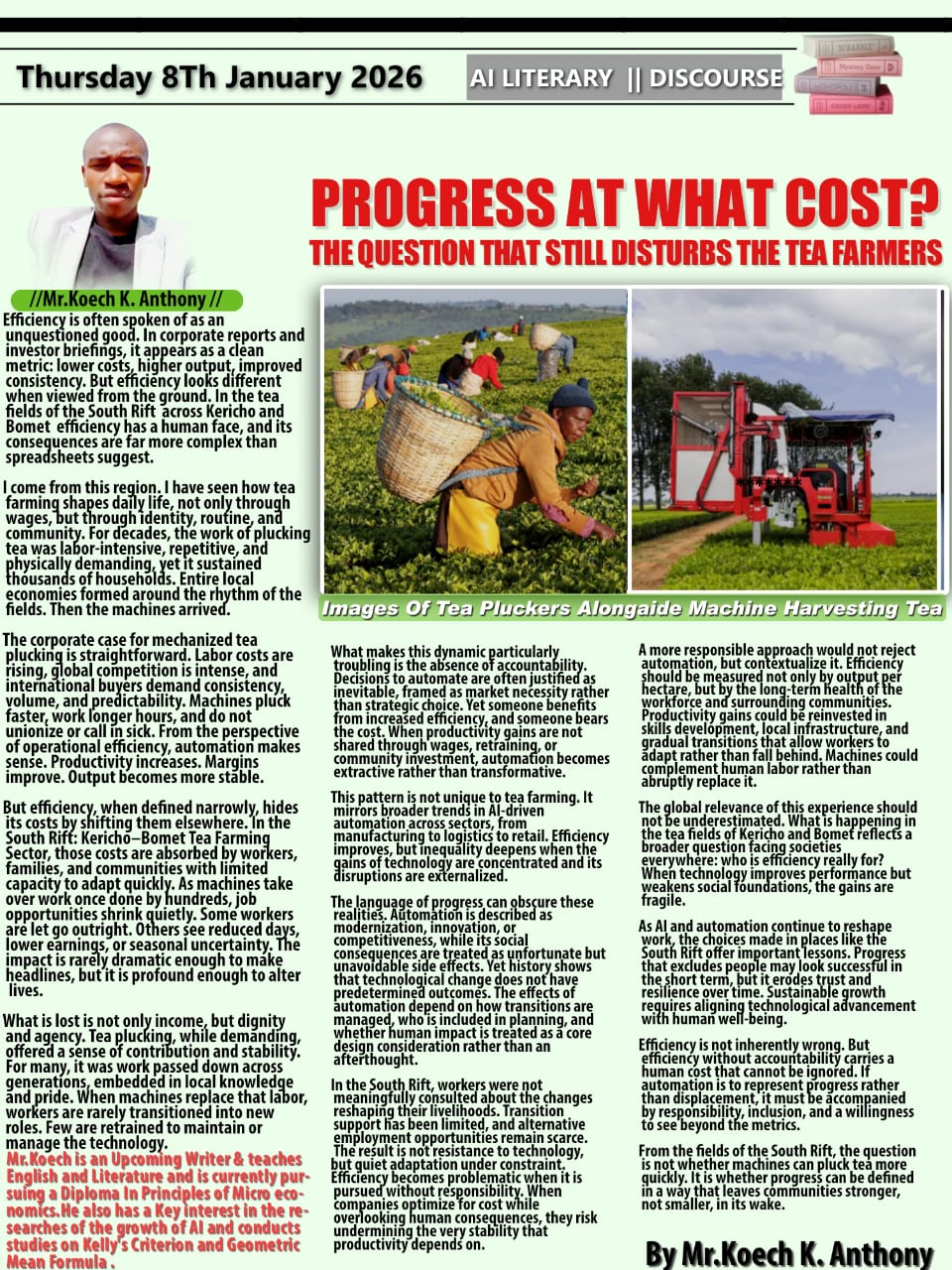

I come from this region. I have seen how tea farming shapes daily life, not only through wages, but through identity, routine, and community. For decades, the work of plucking tea was labor-intensive, repetitive, and physically demanding, yet it sustained thousands of households. Entire local economies formed around the rhythm of the fields. Then the machines arrived.

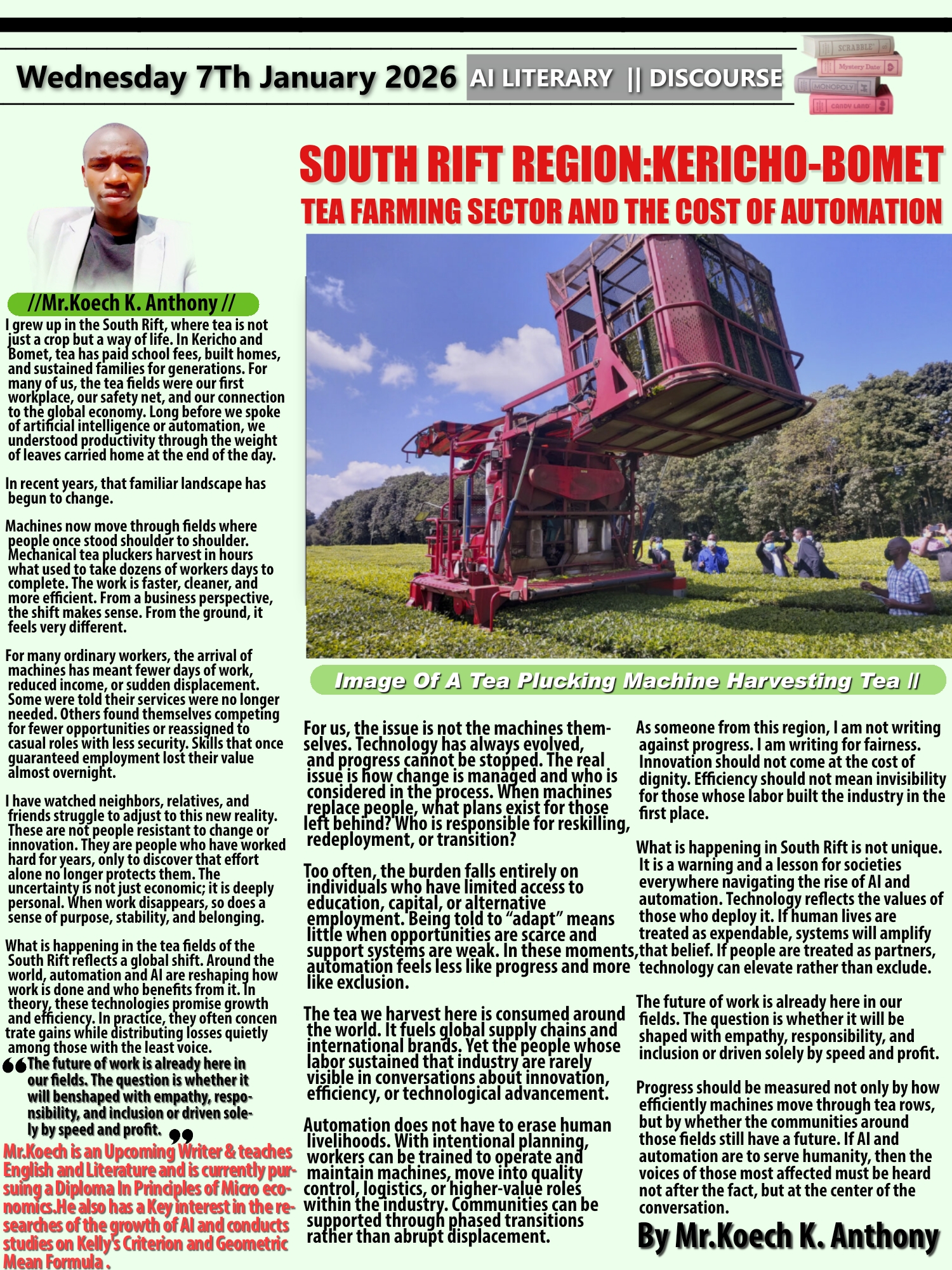

The corporate case for mechanized tea plucking is straightforward. Labor costs are rising, global competition is intense, and international buyers demand consistency, volume, and predictability. Machines pluck faster, work longer hours, and do not unionize or call in sick. From the perspective of operational efficiency, automation makes sense. Productivity increases. Margins improve. Output becomes more stable.

But efficiency, when defined narrowly, hides its costs by shifting them elsewhere. In the South Rift: Kericho–Bomet Tea Farming Sector, those costs are absorbed by workers, families, and communities with limited capacity to adapt quickly. As machines take over work once done by hundreds, job opportunities shrink quietly. Some workers are let go outright. Others see reduced days, lower earnings, or seasonal uncertainty. The impact is rarely dramatic enough to make headlines, but it is profound enough to alter lives.

What is lost is not only income, but dignity and agency. Tea plucking, while demanding, offered a sense of contribution and stability. For many, it was work passed down across generations, embedded in local knowledge and pride. When machines replace that labor, workers are rarely transitioned into new roles. Few are retrained to maintain or manage the technology. The productivity gains accrue upward, while displacement flows downward.

What makes this dynamic particularly troubling is the absence of accountability. Decisions to automate are often justified as inevitable, framed as market necessity rather than strategic choice. Yet someone benefits from increased efficiency, and someone bears the cost. When productivity gains are not shared through wages, retraining, or community investment, automation becomes extractive rather than transformative.

This pattern is not unique to tea farming. It mirrors broader trends in AI-driven automation across sectors, from manufacturing to logistics to retail. Efficiency improves, but inequality deepens when the gains of technology are concentrated and its disruptions are externalized.

The language of progress can obscure these realities. Automation is described as modernization, innovation, or competitiveness, while its social consequences are treated as unfortunate but unavoidable side effects. Yet history shows that technological change does not have predetermined outcomes. The effects of automation depend on how transitions are managed, who is included in planning, and whether human impact is treated as a core design consideration rather than an afterthought.

In the South Rift, workers were not meaningfully consulted about the changes reshaping their livelihoods. Transition support has been limited, and alternative employment opportunities remain scarce. The result is not resistance to technology, but quiet adaptation under constraint. Efficiency becomes problematic when it is pursued without responsibility. When companies optimize for cost while overlooking human consequences, they risk undermining the very stability that productivity depends on.

A more responsible approach would not reject automation, but contextualize it. Efficiency should be measured not only by output per hectare, but by the long-term health of the workforce and surrounding communities. Productivity gains could be reinvested in skills development, local infrastructure, and gradual transitions that allow workers to adapt rather than fall behind. Machines could complement human labor rather than abruptly replace it.

The global relevance of this experience should not be underestimated. What is happening in the tea fields of Kericho and Bomet reflects a broader question facing societies everywhere: who is efficiency really for? When technology improves performance but weakens social foundations, the gains are fragile.

As AI and automation continue to reshape work, the choices made in places like the South Rift offer important lessons. Progress that excludes people may look successful in the short term, but it erodes trust and resilience over time. Sustainable growth requires aligning technological advancement with human well-being.

Efficiency is not inherently wrong. But efficiency without accountability carries a human cost that cannot be ignored. If automation is to represent progress rather than displacement, it must be accompanied by responsibility, inclusion, and a willingness to see beyond the metrics.

From the fields of the South Rift, the question is not whether machines can pluck tea more quickly. It is whether progress can be defined in a way that leaves communities stronger, not smaller, in its wake.

I come from this region. I have seen how tea farming shapes daily life, not only through wages, but through identity, routine, and community. For decades, the work of plucking tea was labor-intensive, repetitive, and physically demanding, yet it sustained thousands of households. Entire local economies formed around the rhythm of the fields. Then the machines arrived.

The corporate case for mechanized tea plucking is straightforward. Labor costs are rising, global competition is intense, and international buyers demand consistency, volume, and predictability. Machines pluck faster, work longer hours, and do not unionize or call in sick. From the perspective of operational efficiency, automation makes sense. Productivity increases. Margins improve. Output becomes more stable.

But efficiency, when defined narrowly, hides its costs by shifting them elsewhere. In the South Rift: Kericho–Bomet Tea Farming Sector, those costs are absorbed by workers, families, and communities with limited capacity to adapt quickly. As machines take over work once done by hundreds, job opportunities shrink quietly. Some workers are let go outright. Others see reduced days, lower earnings, or seasonal uncertainty. The impact is rarely dramatic enough to make headlines, but it is profound enough to alter lives.

What is lost is not only income, but dignity and agency. Tea plucking, while demanding, offered a sense of contribution and stability. For many, it was work passed down across generations, embedded in local knowledge and pride. When machines replace that labor, workers are rarely transitioned into new roles. Few are retrained to maintain or manage the technology. The productivity gains accrue upward, while displacement flows downward.

What makes this dynamic particularly troubling is the absence of accountability. Decisions to automate are often justified as inevitable, framed as market necessity rather than strategic choice. Yet someone benefits from increased efficiency, and someone bears the cost. When productivity gains are not shared through wages, retraining, or community investment, automation becomes extractive rather than transformative.

This pattern is not unique to tea farming. It mirrors broader trends in AI-driven automation across sectors, from manufacturing to logistics to retail. Efficiency improves, but inequality deepens when the gains of technology are concentrated and its disruptions are externalized.

The language of progress can obscure these realities. Automation is described as modernization, innovation, or competitiveness, while its social consequences are treated as unfortunate but unavoidable side effects. Yet history shows that technological change does not have predetermined outcomes. The effects of automation depend on how transitions are managed, who is included in planning, and whether human impact is treated as a core design consideration rather than an afterthought.

In the South Rift, workers were not meaningfully consulted about the changes reshaping their livelihoods. Transition support has been limited, and alternative employment opportunities remain scarce. The result is not resistance to technology, but quiet adaptation under constraint. Efficiency becomes problematic when it is pursued without responsibility. When companies optimize for cost while overlooking human consequences, they risk undermining the very stability that productivity depends on.

A more responsible approach would not reject automation, but contextualize it. Efficiency should be measured not only by output per hectare, but by the long-term health of the workforce and surrounding communities. Productivity gains could be reinvested in skills development, local infrastructure, and gradual transitions that allow workers to adapt rather than fall behind. Machines could complement human labor rather than abruptly replace it.

The global relevance of this experience should not be underestimated. What is happening in the tea fields of Kericho and Bomet reflects a broader question facing societies everywhere: who is efficiency really for? When technology improves performance but weakens social foundations, the gains are fragile.

As AI and automation continue to reshape work, the choices made in places like the South Rift offer important lessons. Progress that excludes people may look successful in the short term, but it erodes trust and resilience over time. Sustainable growth requires aligning technological advancement with human well-being.

Efficiency is not inherently wrong. But efficiency without accountability carries a human cost that cannot be ignored. If automation is to represent progress rather than displacement, it must be accompanied by responsibility, inclusion, and a willingness to see beyond the metrics.

From the fields of the South Rift, the question is not whether machines can pluck tea more quickly. It is whether progress can be defined in a way that leaves communities stronger, not smaller, in its wake.