I grew up in the South Rift, where tea is not just a crop but a way of life. In Kericho and Bomet, tea has paid school fees, built homes, and sustained families for generations. For many of us, the tea fields were our first workplace, our safety net, and our connection to the global economy. Long before we spoke of artificial intelligence or automation, we understood productivity through the weight of leaves carried home at the end of the day.

In recent years, that familiar landscape has begun to change.

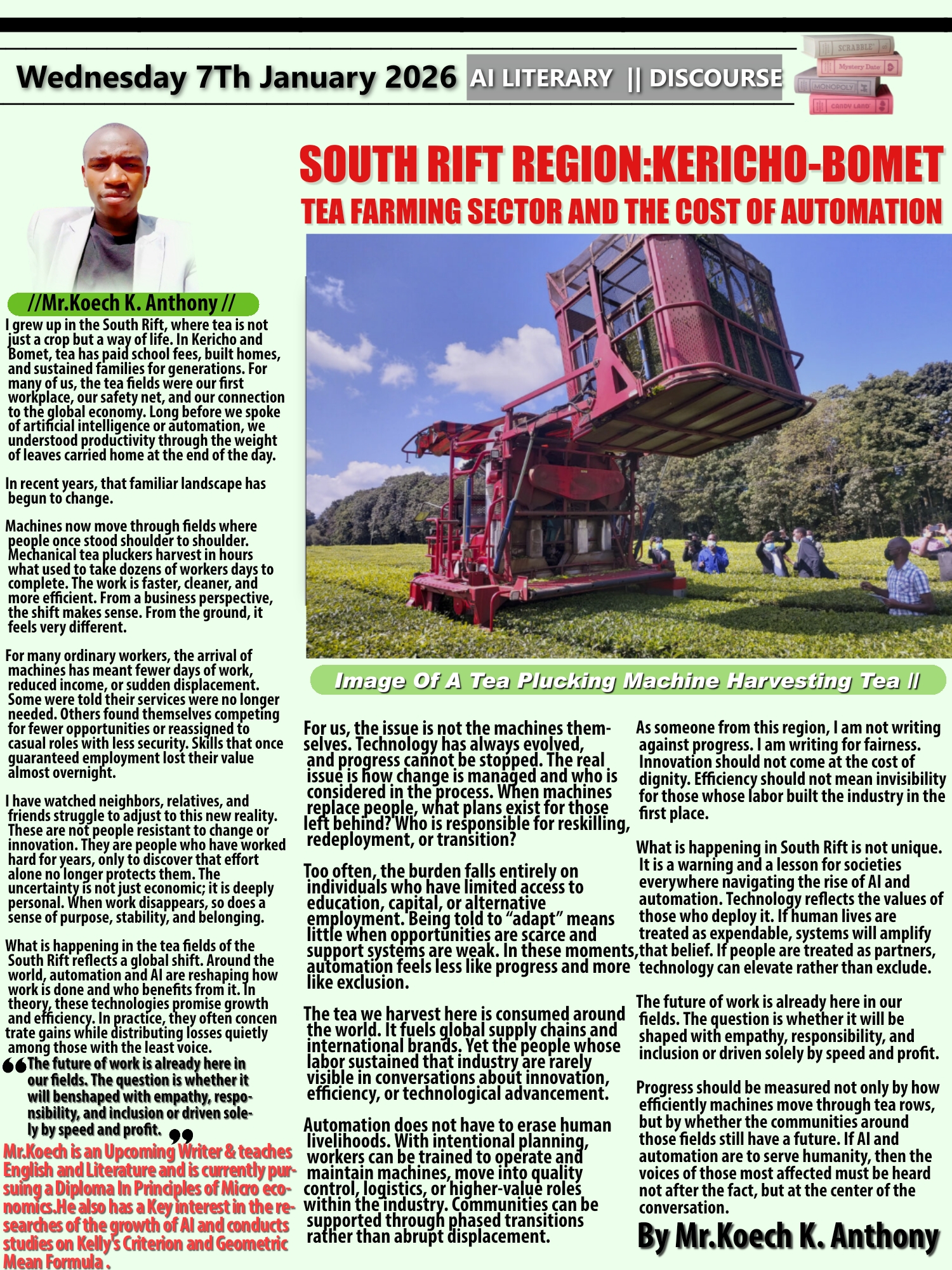

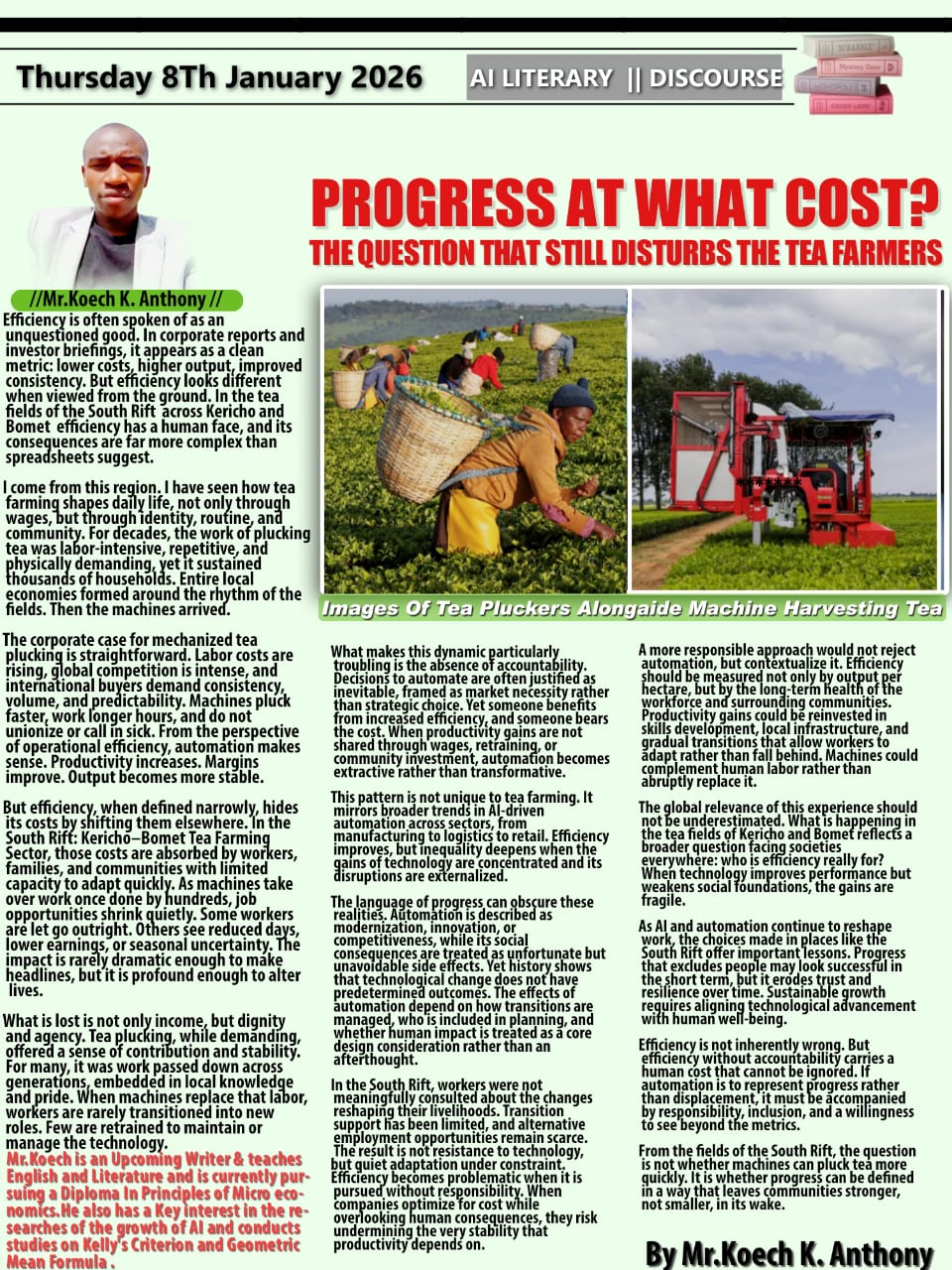

Machines now move through fields where people once stood shoulder to shoulder. Mechanical tea pluckers harvest in hours what used to take dozens of workers days to complete. The work is faster, cleaner, and more efficient. From a business perspective, the shift makes sense. From the ground, it feels very different.

For many ordinary workers, the arrival of machines has meant fewer days of work, reduced income, or sudden displacement. Some were told their services were no longer needed. Others found themselves competing for fewer opportunities or reassigned to casual roles with less security. Skills that once guaranteed employment lost their value almost overnight.

I have watched neighbors, relatives, and friends struggle to adjust to this new reality. These are not people resistant to change or innovation. They are people who have worked hard for years, only to discover that effort alone no longer protects them. The uncertainty is not just economic; it is deeply personal. When work disappears, so does a sense of purpose, stability, and belonging.

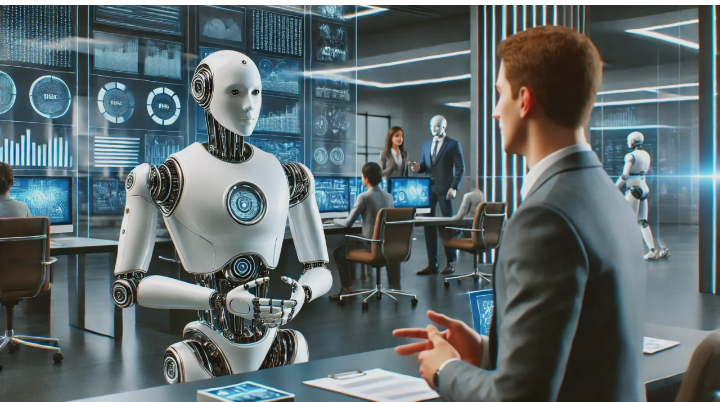

What is happening in the tea fields of the South Rift reflects a global shift. Around the world, automation and AI are reshaping how work is done and who benefits from it. In theory, these technologies promise growth and efficiency. In practice, they often concentrate gains while distributing losses quietly among those with the least voice.

For us, the issue is not the machines themselves. Technology has always evolved, and progress cannot be stopped. The real issue is how change is managed and who is considered in the process. When machines replace people, what plans exist for those left behind? Who is responsible for reskilling, redeployment, or transition?

Too often, the burden falls entirely on individuals who have limited access to education, capital, or alternative employment. Being told to “adapt” means little when opportunities are scarce and support systems are weak. In these moments, automation feels less like progress and more like exclusion.

This shift also exposes a deeper inequality in how power is distributed. Decisions about mechanization are made far from the fields, influenced by global markets, cost pressures, and shareholder expectations. Yet the consequences are lived locally, by workers and families who had no voice in shaping the transition.

The tea we harvest here is consumed around the world. It fuels global supply chains and international brands. Yet the people whose labor sustained that industry are rarely visible in conversations about innovation, efficiency, or technological advancement. Their stories are often treated as collateral damage rather than central considerations.

I believe there is another way forward.

Automation does not have to erase human livelihoods. With intentional planning, workers can be trained to operate and maintain machines, move into quality control, logistics, or higher-value roles within the industry. Communities can be supported through phased transitions rather than abrupt displacement. But these outcomes require commitment from companies, governments, and institutions to invest in people, not just technology.

As someone from this region, I am not writing against progress. I am writing for fairness. Innovation should not come at the cost of dignity. Efficiency should not mean invisibility for those whose labor built the industry in the first place.

What is happening in South Rift is not unique. It is a warning and a lesson for societies everywhere navigating the rise of AI and automation. Technology reflects the values of those who deploy it. If human lives are treated as expendable, systems will amplify that belief. If people are treated as partners, technology can elevate rather than exclude.

The future of work is already here in our fields. The question is whether it will be shaped with empathy, responsibility, and inclusion or driven solely by speed and profit.

Progress should be measured not only by how efficiently machines move through tea rows, but by whether the communities around those fields still have a future. If AI and automation are to serve humanity, then the voices of those most affected must be heard not after the fact, but at the center of the conversation.

In recent years, that familiar landscape has begun to change.

Machines now move through fields where people once stood shoulder to shoulder. Mechanical tea pluckers harvest in hours what used to take dozens of workers days to complete. The work is faster, cleaner, and more efficient. From a business perspective, the shift makes sense. From the ground, it feels very different.

For many ordinary workers, the arrival of machines has meant fewer days of work, reduced income, or sudden displacement. Some were told their services were no longer needed. Others found themselves competing for fewer opportunities or reassigned to casual roles with less security. Skills that once guaranteed employment lost their value almost overnight.

I have watched neighbors, relatives, and friends struggle to adjust to this new reality. These are not people resistant to change or innovation. They are people who have worked hard for years, only to discover that effort alone no longer protects them. The uncertainty is not just economic; it is deeply personal. When work disappears, so does a sense of purpose, stability, and belonging.

What is happening in the tea fields of the South Rift reflects a global shift. Around the world, automation and AI are reshaping how work is done and who benefits from it. In theory, these technologies promise growth and efficiency. In practice, they often concentrate gains while distributing losses quietly among those with the least voice.

For us, the issue is not the machines themselves. Technology has always evolved, and progress cannot be stopped. The real issue is how change is managed and who is considered in the process. When machines replace people, what plans exist for those left behind? Who is responsible for reskilling, redeployment, or transition?

Too often, the burden falls entirely on individuals who have limited access to education, capital, or alternative employment. Being told to “adapt” means little when opportunities are scarce and support systems are weak. In these moments, automation feels less like progress and more like exclusion.

This shift also exposes a deeper inequality in how power is distributed. Decisions about mechanization are made far from the fields, influenced by global markets, cost pressures, and shareholder expectations. Yet the consequences are lived locally, by workers and families who had no voice in shaping the transition.

The tea we harvest here is consumed around the world. It fuels global supply chains and international brands. Yet the people whose labor sustained that industry are rarely visible in conversations about innovation, efficiency, or technological advancement. Their stories are often treated as collateral damage rather than central considerations.

I believe there is another way forward.

Automation does not have to erase human livelihoods. With intentional planning, workers can be trained to operate and maintain machines, move into quality control, logistics, or higher-value roles within the industry. Communities can be supported through phased transitions rather than abrupt displacement. But these outcomes require commitment from companies, governments, and institutions to invest in people, not just technology.

As someone from this region, I am not writing against progress. I am writing for fairness. Innovation should not come at the cost of dignity. Efficiency should not mean invisibility for those whose labor built the industry in the first place.

What is happening in South Rift is not unique. It is a warning and a lesson for societies everywhere navigating the rise of AI and automation. Technology reflects the values of those who deploy it. If human lives are treated as expendable, systems will amplify that belief. If people are treated as partners, technology can elevate rather than exclude.

The future of work is already here in our fields. The question is whether it will be shaped with empathy, responsibility, and inclusion or driven solely by speed and profit.

Progress should be measured not only by how efficiently machines move through tea rows, but by whether the communities around those fields still have a future. If AI and automation are to serve humanity, then the voices of those most affected must be heard not after the fact, but at the center of the conversation.